Unfixed Consciousness/Positive Unconsciousness

Dawn Gaietto, USA - UK

2 December 2021

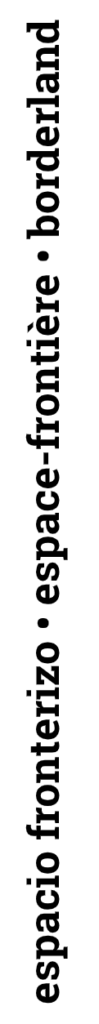

Open Water Preservation Area in August. Digital photography with electronic intervention via Arduino micro-controller and SHT11x sensor. 112 x 264cm.

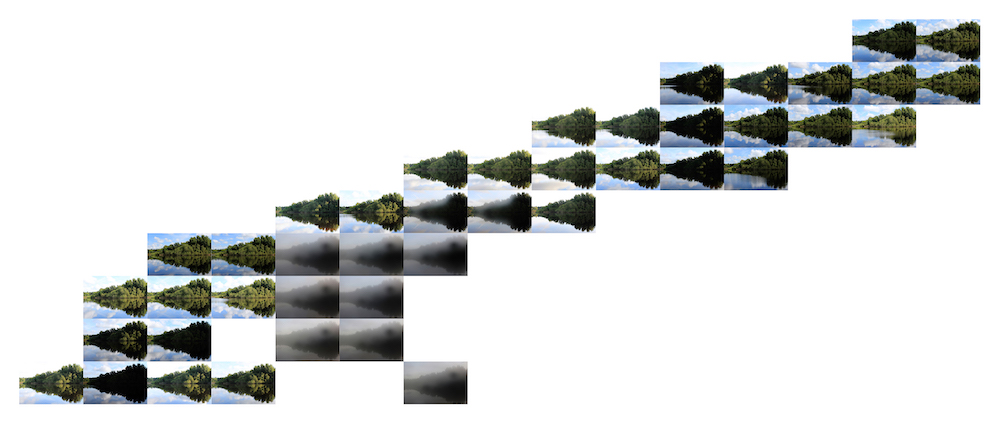

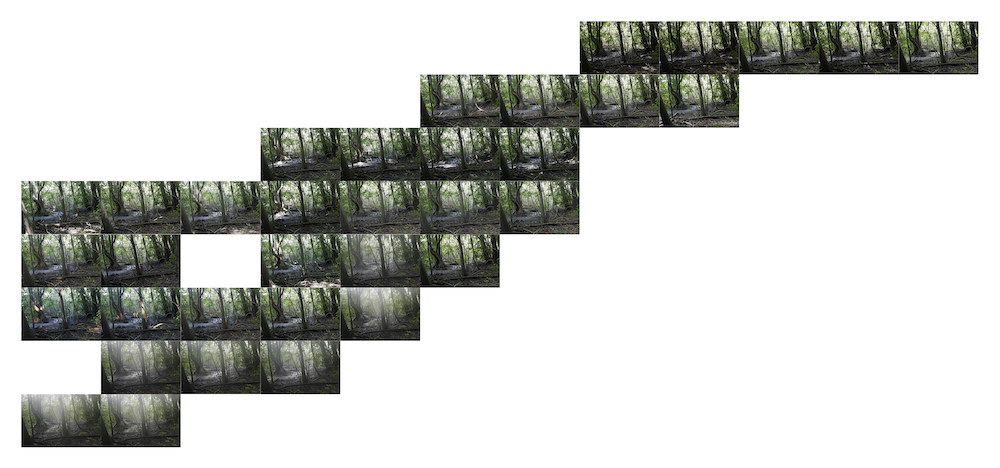

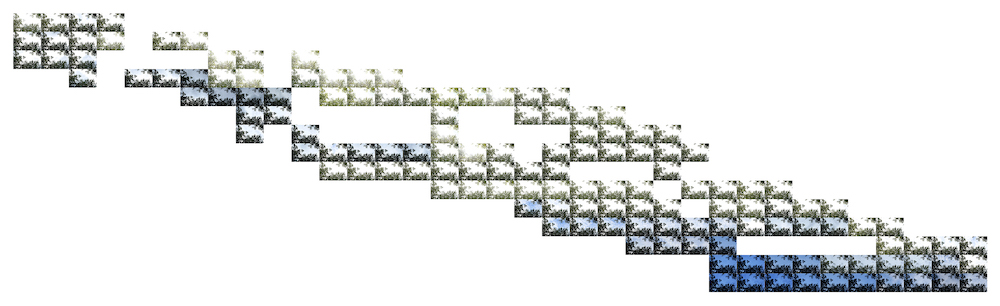

The images in Unfixed Consciousness/Positive Unconsciousness are manifestations of the collective agency between mechanical, technological, and atmospheric elements as well as my own as composer and interpreter. This was done by building an imaging device that triggers the shutter through changes in the temperature and humidity as detected by an SHT11x sensor that queried the environment once a minute. This device was deployed in several archetypical ecosystems throughout Alachua County, Florida, for an eighteen-hour period, one day in each location. In photographing for this project, I selected a variety of ecosystems found in Alachua County both naturally occurring and man-made, to include: pine flatwoods, dry prairie, orchard grounds, active hay field, grazing field, open water, freshwater marsh, hammock, and sand pine scrub. Naturally occurring ecosystems were pictured in the same manner as the man-made systems. All are fragmented visually in the final composite imagery just as they are spatially throughout the landscape matrix of Alachua County and the greater North-Central Florida region. Each location serves as a visual representation of a system that stands to either regulate or significantly modify the local climate due to the significant changes from agricultural development. The measurements of temperature and humidity were selected as parameters for this project due to their relevance to shifting climate in North-Central Florida. As wetlands have been drained for development and agricultural uses, humidity is destabilised and lowers. This lowering of humidity allows for a greater fluctuation in temperature, therefore a shifting frost line, which then pushes agriculture, such as citrus farms, farther south. The locations selected for the images are all key archetypical ecosystems that contribute to modifying their local climates; through the feedback loop the climate continues to modify the land. Here each serial image is constructed from a grid specific to the temperature and humidity variability of the day the images were captured. Each grid places temperature in degrees Celsius on the y-axis and humidity in percent on the x-axis.

Fresh Water Marsh in July. Digital photography with electronic intervention via Arduino micro-controller and SHT11x sensor. 112 x 239cm.

“Positive Unconsciousness” is adapted from Michel Foucault’s introduction to The Order of Things. This phrase is specifically designed to address the oppositional nature between the operations of the unconscious and scientific ordering. Instead of the unconscious disturbing scientific knowledge, the positive unconscious is a “level that eludes the consciousness of the scientist and yet is part of scientific discourse, instead of disputing its validity and seeking to diminish its scientific nature.”[1] In much the same Unfixed Consciousness/Positive Unconsciousness utilises a pseudo-scientific approach to conduct a visual investigation, which seeks to complement current scientific understanding of these climate modifications through a meditative inspection of the ontology of space and place. In addition, the phrase unfixed consciousness works to destabilise the trusted mode of knowing, to suggest that the state of being aware and responsive to one’s surrounding is a fluid state and cannot become responsibly frozen in stasis. To be successfully engaged in knowing anything regarding a space or place that one’s momentary awareness or perception cannot be trusted as a fixed indicator of what has come before and what will come in the future. This phrase Unfixed Consciousness/Positive Unconsciousness works to alienate the viewer from definite knowledge through challenging the notion of an ability to know.

Pine Flat Wood Forest in July. Digital photography with electronic intervention via Arduino micro-controller and SHT11x sensor. 112 x 41cm.

Borrowing from Liz Wells, I am identifying space as an indeterminate expanse of the unknown and place being that which is named, imaged, and thereby owned. “A basic useful definition of landscape, thus, would be vistas encompassing both nature and the changes humans have effected on the natural world.”[2] My landscape images operate in an opposite manner than standard landscapes. Through the repetition, the notion of a unique moment is thwarted, the notion of transcendence is obscured, but yet the images retain a romantic nature. This romanticism stays due to the compositional structure and the gradual variations in light, colour and moisture. The process I deploy relates to the human process of intervention and effect. The apparatus is inserted into the land, and through a systematic approach renders change visible compared to the intervention that often results in visible and invisible change. The transformations from man’s influence and the resultant negative feedback loop become manifest through the series of images. Each landscape is treated as a species, a typographical representation, used in a photographic process that interrogates the condition of the place – an ontological quest to question the condition and stability of the site.

This work draws from the historical lineage of landscape photography, particularly in the relationship between image-making and ownership, inherent from the onset of landscape imagery, derived from European merchants in the late fifteenth century following the introduction of mathematical perspective and oil paints. This use of perspective introduced an ego-centrality to viewing that enhanced the transformation of space into place through picture-making. According to Philip Descola, “Such an ‘objectification of the subjective’ produces a two-fold effect: it creates a distance between man and the world by making the autonomy of things depend upon man; and it systematises and stabilises the external universe even as it confers upon the subject absolute mastery over the organisation of this newly conquered exteriority.”[3] Although it might at first seem that the only locations that retain the realm of space lie beyond the known cosmos or in the sub-atomic structures of life, the primary concern of this project is the transformation of place back towards space. The allowance of ownership and knowing that underlie the determination being place allow for the use and abuse of resources, such as land. Conversely, rejecting that ontological condition and moving land towards space allows for the agency of the land to be recognised, as through the recognition of agency the relationship of “object” is not fixed and allows for a fluidity amongst these things. This shift cannot breach the condition space, but could potentially relocate this condition into a liminal position, allowing a location to bridge the threshold between space and place, acting within both models of thought. To name and to image is to own, to objectify that which is being designated; here the serialised and gridded imagery can escape this fate through its own resistance to the condition of being known.

By creating a vertical topology of atmospheric forces through the collection of data, the serialised images abstract place, although the landscape is not returned to the position of space. The importance of the data is nearly equal to that of the images. The data operates as the theoretical construct for the creation of the images as well as the immediate antecedent for the capture of the images. In operating as the theoretical construct, the data is the connection between the image, the land and the atmosphere. It is an imperative measurement of indeterminate forces of small change that reflect environmental cycles and human interventions. The data is not functioning as science, but is working towards the positive unconsciousness through manifesting data through visual means reaching for an understanding that can tie experience into scientific understanding. The data is working towards an unfixed consciousness by escaping a fixed know-ability, and forcing a new attempt at understanding or perceiving a place with each new encounter given the visual changes indicative of the atmospheric actants reified. Although a tension may seem inherent between chance and scientific data in the capture of the images, to call the system chance is to deny the causality, or to not recognise the relationships within. The proliferation of data through a single day of image capture results in the discarding of hundreds of readings, yet the system of logic retains its accountability through the construction of the grid and the transparency to the mode of construction. It is thus required to embed the data with the corresponding image, retaining the original causal relationship.

Persimmon Orchard in July. Digital photography with electronic intervention via Arduino micro-controller and SHT11x sensor. 112 x 366cm.

Through the activated collective agencies, notions of ownership are resisted transforming into a non-place. This work explores the problem of anthropocentric positions in viewing environmental issues by vacillating between degrees of constructing situations and harnessing existing phenomena to create work in a way that does not provide preference to humans specifically in the context of environmental concerns. As a viewer investigates the works in Unfixed Consciousness/Positive Unconsciousness, they actively defamiliarise themselves with the viewing process. Through the serialised images, one after another obliterates the veracity of the previous image – yet the data retains an authority, making all images equally true at all times. This conundrum disallows the viewer to create a fixed understanding of that place and through erasing the capacity for knowledge erases the capacity for ownership. This process transforms viewing habits, and re-creates active viewers from moment to moment, disrupting viewing processes and habits.

References:

[1] Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), xi.

[2] Wells, Liz. Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity. (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), Kindle Edition, 5%.

[3] Descola, Philippe. Beyond Nature and Culture. Trans. Janet Lloyd. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 59.