The Pluralist School

Jones Irwin, Republic of Ireland

14 November 2024

World is crazier and more of it than we think/ Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion/ A tangerine and spit the pips and feel/ The drunkenness of things being various.

Louis Mac Niece – ‘ Snow’

From 2015-2019, I was seconded as Project Officer on the first state curriculum in values and multi-belief education for primary schools in Ireland (there are currently 29 such Community National Schools). Originally, back in 2008/09, these schools had been set up as ‘emergency schools’, opened to cater for a constituency of children who couldn’t find a place in the Catholic dominated primary system. Most of the children concerned were from international/immigrant backgrounds, newly arrived in the Republic of Ireland and falling foul of the ‘Catholics first’ policy of school enrolment.

Figure 1 Community National Schools in the Republic of Ireland follow the Goodness Me, Goodness You curriculum which is the first multi-belief and values curriculum in the history of the state. There are now 29 such state schools across the country.

For more than a decade previously, I had been involved (as a philosopher of education) in advocating for the need for change in the Irish system, where even today 96% of our primary schools are denominationally run. Specific colleagues and I fought over several years for transformation of the teacher education system and for related change at the level of schooling, and at the heart of this philosophical and values-led movement was a vision of affirmation of difference (rather than fear of the latter), a saying yes to pluralism. In this short essay, I will explore how this political and educational project also had deep aesthetic allegiances, and how we might think about the relation between education and literature across borders, most particularly the form of poetry and poetics.

MacNiece’s poem Snow (excerpt included above as an epigram) became a continuing recourse for me during this period. But its more primitive evocation of the experience of (natural) difference – ‘the drunkenness of things being various’ – needed a more formal scaffold to defend an application to education and pedagogy. Bhikhu Parekh’s work (Parekh 2005) has been at the heart of the UK and international debate on pluralism in education and the wider society over the last two decades. His groundbreaking text, Rethinking Multiculturalism, foregrounds some of the key issues of tension in the problematic of ‘multiculturalism’.

‘Multicultural societies throw up problems that have no parallel in history. They need to find ways of reconciling unity and diversity, being inclusive without being assimilationist, cherishing plural cultural identities without weakening the precious identity of shared citizenship’ (Parekh 2005).

Being inclusive without being assimilationist – schools are often the first interface for this experience of multiculturalism, in that the segregated housing policy for immigrants which is put forward by most Western governments means that children tend to meet across cultures and difference first in school, rather than home community. Policy makers often underestimate the nuance and subtlety required, let us say the artistry required, to translate this vision into a school context. As Terence Mc Laughlin notes, ‘a school is engaged in a practical enterprise of great complexity which calls for many forms of practical knowledge’ (Mc Laughlin 2008: 204).

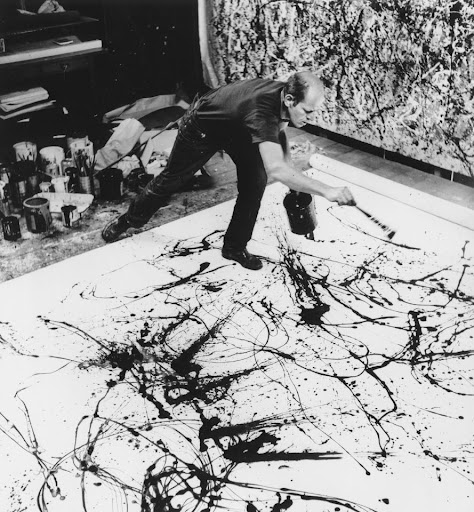

While challenging, this provides a great possibility for our education systems to lead the way on a more positive and affirmative understanding and practice. In this context, we can foreground The Pluralist School as a concept and as an aspiration. In my work in teacher-education, I tend to employ examples from Art to explore perceptions and pre-conceptions of students. The Action-Painting of Jackson Pollock is an evocative resource, beginning with an image of him working on a large blank canvas, across the studio floor. This is life and school as tabula rasa, blank slate, open to fresh ideas and experimentation. Of course, this image is somewhat utopian in that contexts are rarely free of original bias or prejudice, often an inherent bias on behalf of the native vs the newcomer (although it can also be the other way, mistrust of the native).

As a more realistic picture of endemic tensions, I deploy an etching from Goya, As If They Were Another Breed, depicting in stark division the exploitation of the Spanish people (subjugated, starved, in some cases to death) by their French colonial masters. This leads to discussion on political division, issues of racism in education and power dynamics between oppressor and oppressed. As a third complicating image, I introduce Pollock’s powerful canvas from the ‘50s, Convergence. This expresses an organic unity and harmony which emerges from within an affirmation of difference (and sometimes disharmony). Here we have an artistic representation for the concepts of Parekh – ‘cherishing plural cultural identities without weakening the precious identity of shared citizenship’ (Parekh 2005).

Figure 2 Jackson Pollock in the midst of Action Painting. Photograph: Hans Namuth, 1950.

We might also think of Pollock as leading us back to MacNiece and the more tense ambiguous harmony of Snow – ‘World is crazier and more of it than we think/ Incorrigibly plural’. But despite the tensions of the situation we faced in the Irish context, the work with Community National Schools was quite the success. There are now, in 2024, 29 such schools in the Republic of Ireland, staffed by capable and visionary teachers and principals, backed by newly confident communities, redeveloping the sense of what education and identity means in Twenty-First century Ireland. One of the stories we employed in the curriculum development was Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. Michael Rosen has noted how this book was repressed (banned) in the UK for several years after its original publication in the United States: ‘at a surface level, this was on account of it being deemed too frightening for very young children, but perhaps they also sensed that it was a book which showed a child’s destructive feelings without these feelings being punished’.

While agreeing with Rosen (whose vision of progressive education and childhood is to be lauded), we might also say there is more than destruction in Sendak’s children. We perhaps should take some courage from the central child figure Max, in this text:

And when he came to the place where the wild things are

they roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth

and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws

till Max said “BE STILL!”

and tamed them with the magic trick

of staring into all their yellow eyes without blinking once

and they were frightened and called him the most wild thing of all

and made him king of all wild things.

If we are looking to examples of this vision deployed in more contemporary times, where we confront the monsters of our innermost and primal fears, as individuals and as communities , we can perhaps cite the example in literature of a certain psychogeography. This concept originates with the Situationist (and Lettrist) understanding of psychogeography, emerging with the French theorist Guy Debord (seminal for the May ’68 events), as ‘the study of the specific effects of the geo-graphical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals’ (quoted Coverley 2006: 10). As Merlin Coverley notes, ‘psychogeography is, as the name suggests, the point at which psychology and geography collide, a means of exploring the behavioural impact of urban place’ (Coverley 2006: 10). There is also a cultural and philosophical debt here to Surrealism and to Dadaism (earlier to the Symbolism of Rimbaud and Baudelaire), a debt which accrues also up to the Punk movement in music and in literature, which similarly deploys this ‘psycho-‘ or ‘damned’ dynamic (Hell 2008). This methodology becomes a conducive technique for artists and writers to develop a new philosophical practice of everyday life, and literature (metafiction, poetics etc) becomes a particular pathway to explore. Thus, we find ourselves within a pluralist literary context, enabling various perspectives and lenses on our perception of the world, seeking to work against what Eric Fromm used to call the ‘fear of freedom’.

We have examples of how this radical aesthetic has translated very successfully and powerfully into everyday practice, from relatively recent history. Guy Debord’s vision was indeed seminal for the May ’68 events. His presence as an intellectual subversive at the University of Nanterre on the outskirts of Paris (under the reciprocal tutelage of luminaries such as Henri Lefebvre and Jean Francois Lyotard no less) was a crucial catalyst for the ’68 events. The slogans and posters of ’68 may be simple, but this is also deceptive. We should rather look to the importance of the political ideas expressed aesthetically as having immediate impact in the late 1960s, but also at the insight of the underlying Situationist philosophy which influenced them. We need to remember the contemporary significance of Situationist theory, especially in the context of the renewal of Marxist thought in the 21st century. This renewed Leftist critique of capitalism emerges as articulated through newer social and political movements of the current times, particularly through the political philosophy of Slavoj Žižek and his auto-critique of the Former Yugoslavia. It remains especially relevant in our present times of crisis and social apocalypse (I write this text on the cusp of the American Presidential Elections in early November 2024).

But the avowal of a critique of ideology also comes with a significant philosophical health warning from the Situationists and this is a self-satire that is also prominent in ’68 and again visible in the posters. ‘Participation – All the Better to Eat You With My Children!’ (Vermès & Kugelberg, 2011, p. 6).

How the dream of emancipation and the empowerment of the underclass (or ‘the children’ here as another example of infantilism) runs aground! Perhaps all this talk of increasing radicalisation and democratisation (‘we are so much more radical than you are’ or ‘’Oh look at how pluralist our school is’!) may be just alternate ruses to co-opt any potentially transformative action into complicity with the forces of power. This poster and this declaration also contains an angry and somewhat disillusioned question; what then would authentic participation in the revolution be, what would it look like? What could it possibly feel like in the real world beyond the spectacle? Is there even such a place, today, in 2024?

Figure 3 Participation - All the Better to Eat You With My Children! Reprinted from Vermès & Kugelberg (2011: 6).

Freire thinks there is such a Utopia of pluralism (and a possible real-time school) and describes it thus: ‘the creation of multiculturality; it calls for a certain educational practice. It calls for a new ethics, founded on respect for differences, a unity in differences’ (Freire 1992: 137). Is it too much to suggest that our own Community National Schools in Ireland might have been one group of such (29) experiments, in this case doing quite well, thank you very much?

Figure 4 Repainting of Picasso’s Guernica by AntiCapitalist Students Thessaloniki, hanging in The Rectory, Aristotle Thessaloniki University, Greece, July 2024.

This is certainly a vision we would like to endorse. But its achievement cannot be smooth or linear. In present times, the emergence of change and of authentic participation will not be easily won. It will require protest but also dialogue and the goal of mutual understanding across differing worldviews. To conclude this particular essay, I add a series of haiku I developed under the inspiration of another such related but particular context of struggle and critique, the context of student protest in Thessaloniki, Greece. I visited Thessaloniki in July 2024 and interviewed the main student leaders and we are currently developing a book project on their vision for a renewed and public (state) University in Greece contra the forces which seek to reify education into a commodity for sale. I came away inspired by their energy, vision and affirmative joy in revolt (also their humour and generosity of spirit) and wrote the haiku in tribute. Their ideas and their practice show how we might connect a vision of the pluralist school to the pluralist university and, of course, to an authentically multicultural and (unfearful) differentiated society.

Student Revolt Thessaloniki Haikus [i]

I interviewed Alexis

Who told me about riots

– against the privatised University

At Aristotle Thessaloniki

Anarchists stage an occupation

– no to commercial education

Students repainted Guernica

To avoid the same fate

– it hangs in the Rectorate

AntiCapitalists gather in the Steki

Iced coffee for the Revolution

– caffeine helps with enlightenment

In the city it hits 38 degrees

The Gaza demo does Aristotelous

– black and red flags rise

Petros sees an uncertain future

Tales of hurt and of exploitation

– oppression without redemption

Together we read Kropotkin

Later Marx and Bakunin

– literature is a burning sun

Aliki thinks I’m mad

To think this at Halkidiki

– student revolt will win out

(Irwin 2025)

[i] Mignolo Arts/Pinky Thinker Press in New Jersey, US have developed an inter-disciplinary translation of this haiku which also evinces a concern for borders and border-disciplinary crossings. Thanks to Mignolo and especially to Charly Santagado for their inspiring work on this. This work evinces a pluralist form of literature or a pluralist iteration of what Jacques Derrida called ‘l’écriture’. For the Mignolo shared performance of the haiku, see here: https://www.mignolo.art/convosintranslation/jonesirwin.

References

Boroditskaya, Marina and Rosen, Michael (2015) “Children’s Poetry and Politics: A Conversation,” in Dugdale, ed., Modern Poetry in Translation, 67-74.

Coverley, Merlin (2006) Psychogeography. Oldcastle Books, London.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Continuum

Irwin, Jones (2016) ‘Aesthetic-Ethical-Religious: Goodness Me! Goodness You! Curriculum With A Nod To Where The Wild Things Are’ in Breac. A Digital Journal of Irish Studies. University of Notre Dame, USA.

Irwin, Jones (2025) Deep Image or A Painting By Jeffrey Dahmer (Chapbook). Tofu Ink Press, California, USA (forthcoming)

Mac Niece, Louis (2002) Collected Poems. Penguin. London.

Mc Laughlin, T.H. (2008) ‘The Burdens and Dilemmas of Common Schooling’ in Carr, D, Halstead, M and Pring, R. (eds) Liberalism, Education and Schooling, Essays by T.H.Mc Laughlin (2008) Imprint, Exeter.

Parekh, B. (2005) Rethinking Multiculturalism. Routledge, London.

Sendak, Maurice (2000) Where the Wild Things Are (New York: Random House)

Vermès, P. & Kugelberg, J. (Eds.). (2011). La beauté est dans la rue. London

Žižek, S. (1989). The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso.