The Original of: Hudinilson Jr. –part 1

Manuela Irarrázabal, Chile

20 February 2021

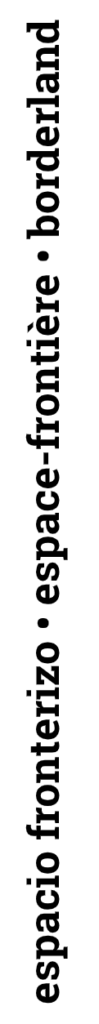

Hudinilson Jr., Exercício de me ver I (Exercise of seeing myself I), 1980. Courtesy: Pinacoteca de São Paulo. Photograph: Isabella Matheus.

I[1]

The dichotomy between original and copy as a means for establishing hierarchies of value is deeply ingrained in Western cultures. Plato’s Theory of Ideas is a good old example: what we consider reality is simply a replica of pure Forms that we cannot perceive with our senses. It could be argued that this dichotomy becomes particularly strong in the case of the visual arts, where the value rests heavily on the object –the original one, needless to say. Unlike other forms of art, like music, cinema or literature, where value can also be thought of as a function of iterability and reproductivity, the visual arts enjoy a particularly fetishistic nature. What matters is not the number of copies an author sells, as with books or albums, but a degree of uniqueness. As often stressed in Critical Theory, when value (always an abstraction) is materialised in an object, it carries implications for the marketisation, dissemination, and democratisation of that object.

The way we speak is telling. When we see a Picasso, leaving the obvious metonymy at work aside, our focus of reference is on the originality of the piece or the value attached to it by falling under Picasso’s authorship. This use of language does not apply to lesser-known artists – the expression ‘I have a XX hanging on my living room’ would sound presumptuous, if not ridiculous, if XX is not a renowned artist. The reference to the author, which is given by the originality of the piece, is a mark of status and of its inherent susceptibility to being copied or faked; in that sense, XX is not really fakeable.

As with the delineation of any border, both sides are interdependent: there cannot be an original of something that is not liable to being copied. Yet, that very liability makes it more valuable—a remark that is hardly new. In F for Fake, Orson Welles suggests that the value attributed to a piece of art is highly mediated by a system of experts relying on their abilities to discern what is authentic from what is fake. Does it even make sense to pose the question of a fake Picasso being better than an original one?

The debate on ‘Original vs. Copy’ in Art Theory may not be new: it is continuously challenged by artists doing Pop Art, Performance or Live Art, and intensified by the coming of Digital Art and Computer-generated Art. No matter how interesting these discussions may be, the art market, with its machinery of experts, relies on notions of authorship, originality, and uniqueness to establish hierarchies of value—and to sell. A certificate of authenticity in digital art, issued by the author, the gallery or whoever is granted the authority for that, or now NFT/blockchain technology, is key. That is, it is key for selling, since the piece of binary code behind the piece of work is the same for the original and the copy, making the distinction superfluous.

The visual arts enjoy a particularly fetishist existence, and yet collectors hunt for books’ first editions, manuscripts, old scores, LPs, anything that can count as ‘the original’, whether it is music, cinema, or literature. This is a fair indication that the quest for the original is far from being an exclusivity of the visual arts. Branding something as ‘Limited/Deluxe/Collector’s Edition’ works only too well as a marketing tool; so much that it sounds unoriginal already –we see it applied to wine, chocolates, cars, clothes, DVDs, videogames…

II

Hudinilson Jr. (1957-2013) belongs to the Xerox Group that emerged in the 70’s in Brazil. The context was a repressive dictatorship that made the already difficult position of discriminated groups, such as gay people, in a heavily segregated society even worse. As part of an effort to modernise the country, efficiency being at the core of the Neoliberal ideology at place, the military government imported a huge number of Xerox-914 machines, sending them to São Paulo. The Xerox Group started making Copy Art or Xerography by using these machines and standard copier paper.[2]

While materials for more conventional types of artistic printing, such as serigraphy or lithography, were unaffordable to them, access to these machines, normally intended for bureaucratic purposes, allowed them to create and distribute their work while remaining on the margins of society and the art market.

The collapse of the categories of ‘original’ and ‘copy’ embraced by the Xerox Group in Brazil (Xerox Art in California precedes them) reflected their derision for standard practises related to art and its marketisation. Discourses at the time exposed anxieties about the serialisation and mechanisation of art in the face of new technologies –photography had somehow fought its way into being considered as ‘real’ art. Xerox Art was not even close to that in the main artistic circles. The fact that images could be created with mere replicating devices had strengthened the prevailing views that the value of art must be located in individual talent—what matter was the skills displayed, the uniqueness of the piece and, crucially, its irreplaceability. The very fact that copying could be accomplished so easily deepened the quest for something that could create an exclusive link between the author and the piece, and a signature that would bear witness to it. Debate on this matter, among art experts, theoreticians, and artists themselves, was increasingly heated.

By contrast, Copy Art played with pastiches, parodies, and digressions. They adopted practises such as signing their pieces, the original/copies, with rubber stamps or adding an infinity symbol (∞) instead of a serial number, thus ridiculing the mainstream’s fetishisation of the original. In one of their exhibitions, instead of a catalogue with reproductions, they circulated a portfolio with photocopies: why should anybody get a reproduction when they can get originals?

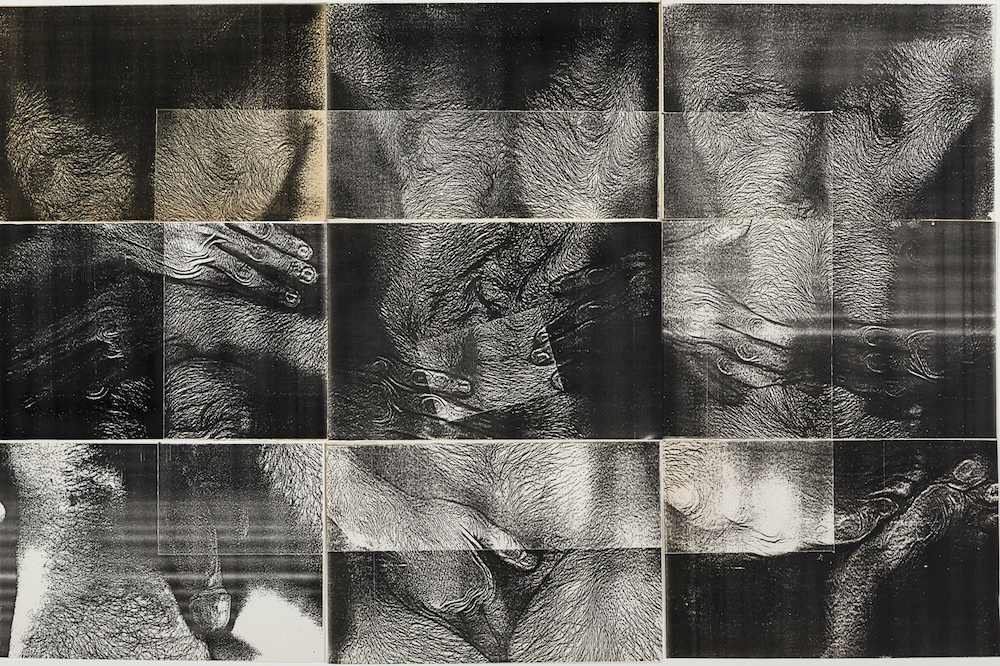

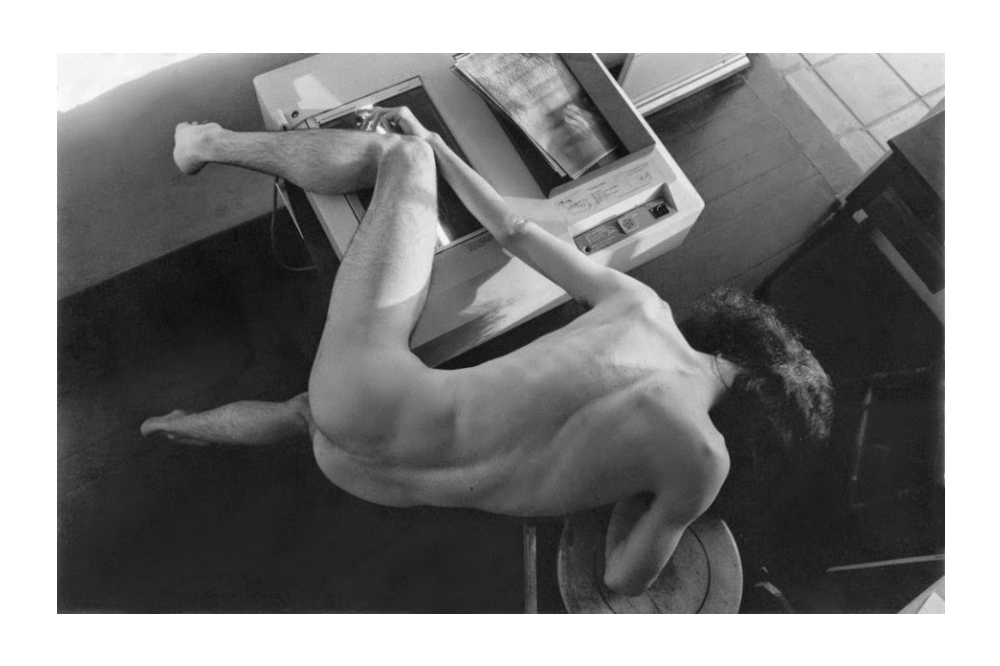

The work of Hudinilson Jr. not only challenged the hegemony of the original, but also the rigid sexual norms under dictatorship. It often depicted an eroticised male nude body, suggesting a gay, hedonistic gaze which contested long-entrenched sexual norms according to which the only acceptable object of desire and consumption was the nude female body. The military regime was particularly intent on suppressing queerness and in response he copied, amplified and multiplied his own queer body. Sitting or lying on the platen, Hudinilson Jr. used the machine as a means for self-exploration and self-exposure, enabling him to both capture places that were otherwise impossible to reach and simulate a sexual act with the machine.

Hudinilson Jr., documentation of the performance “'Narcisse' Exercício de Me Ver II [Exercise of seeing myself II)", 1982. Courtesy of Galeria Jaqueline Martins.

Two of Hudinilson Jr.’s main projects were Exercício de me ver (1981) (Exercise on seeing myself) and Narcisse/Estudo para autorretrato (1984) (Narcissus/Study for Self-portrait), thus underscoring the idea that the machine that reproduces his image allows for self-exploration whilst also driving erotism. There are parallels with ancient Greco-Roman texts, where mirrors (the quintessential tool for reproducing your own image) function as metaphors either for self-knowledge or for narcissistic tendencies, and as a warning about the dangers of excessive concern about oneself. The work of Hudinilson Jr. is also a reminder of how the border between the two can blur.

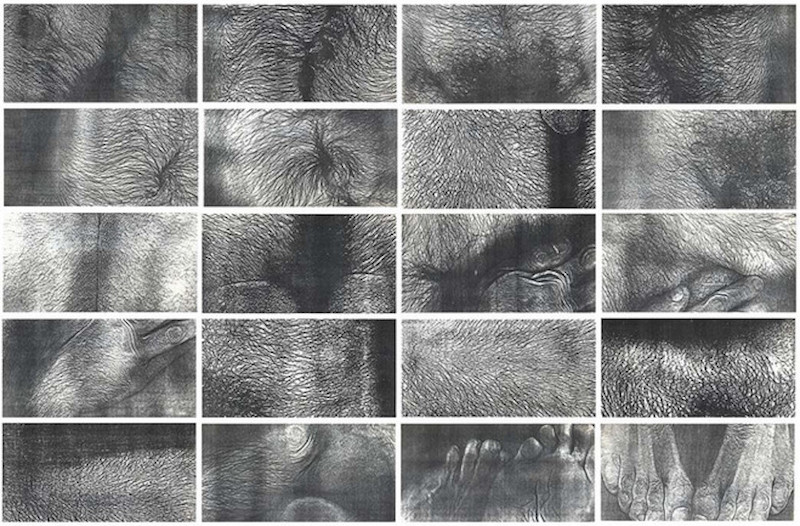

Hudinilson Jr. used the stark image made by Xerox-914s to reproduce and amplify hair, skin, orifices and genitalia. The photocopy of his own nude body goes through reiterative reproductions that he cuts, glues, and copies again. The copy distorts, enlarges and flattens, creating a new image. The process of reiterative copies and distortions is precisely the one needed to reveal the particularity of his experience (‘my story’ in his own words)[3] and express condemnation, as, for example, when he used X-rays from his own broken leg, the result of a homophobic attack suffered by him, as part of his (Des)Construir Narciso ((De)constructing Narcissus) series.[4] His images not only show an erotised body, as literature about his works tends to remark; they also show and enlarge things that society overshadows: the enlarged skin, hair and orifices of a gay person. The copying self-exploratory/narcissistic tool is an act of irreverence.

Hudinilson Jr., Sem titulo, 1981. Courtesy of Galeria Jaqueline Martins.

Hudinilson Jr. died in poverty, exhaustion, and illness. Today, posthumously, his work is highly priced and exhibited in places like Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, MoMA, Tate, and MALBA. His ‘copies’ finally became ‘originals’.

This is the end of the first part of a two-part essay. Read the second part here.

[1] This essay is indebted to Maisie Harrison’s and Gabriella Wyer’s insightful comments on a first draft.

[2] Mari Rodríguez Binnie (2019) ‘Dissident Bodies’, Third Text. DOI: 10.1080/09528822.2019.1669362.

[3] ‘Interview with artist Hudinilson Jr’, conducted between 2011 and 2013 by Vitor Butkus. https://vimeo.com/214683033.

[4] Paulo Miyada (2021) ‘To Caress, to Fondle, to Covet: Hudinilson Jr.’, Mousse Magazine 72. http://moussemagazine.it/hudinilson-jr-paulo-miyada-2020/