out late and dirty: curfews and the covid city –part 1

Sabina Andron, UK

3 March 2021

'Curfew – Social Cleansing': pre-pandemic poster by street prankster Dr D in Aberdeen 2019, photo by Jon Reid, courtesy of Dr D.

This is Part I of a two-part article. Read Part II here.

There is no public life without disorder.

One of the main losses resulting from covid[1] lockdowns and curfews has been that of rights to disorder, mischief, debauchery, and any number of afterhours activities which take place among people. These activities energise city streets, buildings, back alleys and transport infrastructures in disorderly and improper ways. They tend to produce moral panics about civility and propriety in the media, and generate paranoid control mechanisms from local and national governments, yet they are intrinsic to the lives of cities and many of their inhabitants. This two-part essay is a nod to the late nights, dodgy activities, and side hustles that pump adrenaline and energy into the veins of cities, the kind of energy that comes from self-determination and exposure to the unknown; the collective energy of producing and occupying spaces of circulation and intersection, which has been altogether cancelled by the damaging ‘fantasy of control’ of curfews, restrictions, and lockdowns (Caduff 2020). This essay pays homage to the necessary energy of disorder and its generative capacity, by showing some of its spaces and imagining the many unseen others.

What makes this pandemic unprecedented is not the virus but the response to it (Caduff 2020). Lockdowns have been imposed in many parts of the world as ‘new regime[s] of truth spanning scientific, governmental and socio-cultural beliefs’ (Arabindoo 2020), blanket responses to unique individual conditions which have become dangerous by default, or irrelevant at best. To respond to the thresholds theme of the new Borderland journal, I propose to inhabit the time-space of curfews and lockdowns, and confront their moral authority through a series of visual and written arguments. I will ask the reader to join me in the exercise of separating the virus from the lockdown, or the biological threat from its biopolitical management; and reflect for a few minutes on the urban behaviours and processes which, like many of our regular activities, have been prohibited, outlawed, and morally reprimanded.

Sitting on park benches became a form of transgression and disobedience. Clissold Park, April 2020. Photograph: Sabina Andron.

Afterhours threats

In 1660, King Charles II issued a London-wide curfew to prevent the ‘vitious, debauched and prophane’ behaviour of ‘Persons, whose Licentious Appetites, are neither under the Command of any Reason, nor willing to be restrained by any Laws, Men that glory in their shame, and make this onely use of Virtuous Examples to deride them’ (England and Wales Sovereign, 1660). The measure was to close all public houses by 9pm, preventing any further public activities, and therefore curtailing any potentially licentious behaviour therein.

In Victorian England and the European Middle Ages, curfew (from the French couvre feu) was usually signalled by tolling a bell, to warn inhabitants to extinguish or cover their fires, and later to stay indoors (OED online, 2020; Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2016). This was to protect the timber city from the hazard of domestic fire, but also to protect the streets from the unwanted coming together of bodies (read also: the coming together of unwanted bodies). Modern day curfew orders are usually states of exception (Agamben 2005) associated with war, civil unrest and other major societal disruption, yet there is one characteristic that all curfews have in common: the imperative to contain human disorder and to control human disobedience and undesirability. They are an instrument for keeping certain people away from others under missions of safety, civility, morality, and health.

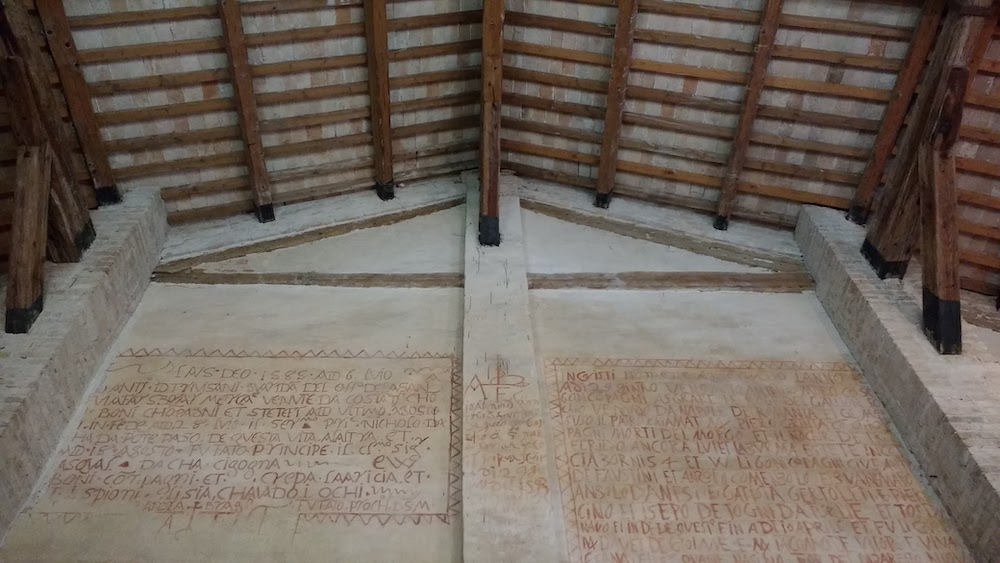

Immunity architectures: The 16th ct Tezon Grande plague quarantine centre on the Venetian island Lazzaretto Nuovo. September 2016. Photograph: Sabina Andron.

Immunity archives: Wall writing documenting merchants, sailors and the presence of the Health Authority of the Serrenissima (Venetian Empire) inside the Tezon Grande quarantine building. September 2016. Photograph: Sabina Andron.

Immunity designs: Doctor’s mask with plant-filters to protect from inhaling contaminated air. September 2016. Photograph: Sabina Andron.

Disobedience and containment

Legally in the UK a curfew is a requirement that an offender remains at a specified place at particular times (Law, 2018), and is associated with anti-social behaviour and disorderly youths. The Crime and Disorder Act of 1998 introduced youth curfews based on the control and deterrence of lawlessness and moral decline; while the 2003 Anti-Social Behaviour Act gave the police powers to hold and escort home unaccompanied minors under the age of 16, between 9PM and 6AM. Legal scholar Alexander Korecky points out how these curfews ‘make each minor out past curfew hours subject to criminal or civil penalties, no matter the activity in which he or she engages’ (Korecky 2016: 856-7), and reflects that ‘we would never accept the idea of reducing adult crime by instituting an adult curfew’ (857). Fast forward to 2020 UK, and the pandemic responses generate a different reality: it is now a crime to take one’s body into a public space except for very specific reasons, and bodies are threatening to others because of the disobedience of being in public. There is no conclusive evidence that youth curfew laws have an effect on reducing youth crime rates (McDowall et al 2000, Levesque 2011); and I have yet to find a study which demonstrates the effect of covid lockdown curfews on anything other than a fear-fuelled appearance of discipline, through the illusory absence of bodies from public spaces during curfew hours.[2]

Unsurprisingly, such youth curfew laws, much like the covid-related curfews and lockdowns, have come under heavy constitutional scrutiny. For example, to test the constitutionality of youth curfew laws in the US (where over 85% of cities with more than 180,000 inhabitants had a youth curfew in place in 2009!), the law must be justified by a compelling governmental interest and must advance that interest through the least restrictive means (Korecky 2016: 835). It seems hardly justifiable to control the movement of more than 85% of urban youths as a non-restrictive measure – much like the blanket lockdowns and curfews which were imposed on half the population of the world in 2020[3] (Sandford 2020).

Bodies are more than their antibodies, and their health is in community, not just in immunity: BLM protest in Parliament Square, London, June 2020. Photograph: Sabina Andron.

Night-time covid curfews have been imposed in countries on all continents since the beginning of 2020, and one need only launch a quick internet search to see examples from France, Greece, Morocco, India, Germany, Kenya, Israel, Australia, South Korea, Belgium, Slovenia, Spain, Egypt, Sudan or Peru –which imposed restrictions on night-time movement of people nationally or locally between 7/8/9PM – 5/6AM, as well as closures of bars and restaurants and bans on public drinking, where those were not already in place. Whereas these interdictions applied to all cases except for medical emergencies, Turkey was the only country worldwide to apply an age-stratified curfew, for seniors older than 65 years and for children and youth younger than 20 years (Kanbur and Akgül, 2020). Human Rights Watch have accused police officers of murder and excessive force in the enforcement of the curfew in Kenya (Kenya – Nationwide Curfew Extended, 2020); and 2020 curfews in the US were also imposed to contain the Black Lives Matter protests after George Floyd’s murder.

This of course is not new. A racialised curfew instituted in 19th century Rio de Janeiro for over 60 years was selectively applied to enslaved persons and those who could be mistaken for slaves, such as free persons of African descent. ‘The well-off were explicitly exempted,’ writes historian Amy Chazkel, ‘and lighter-skinned people appear to have been implicitly so’ (2020: 111). The spaces of curfew were not just streets, but also interiors such as tavernas, shops, bars, or gambling houses, or indeed any space which was not domestic, whose ‘moral standard’ had to be kept.

Similarly now, shared spaces have become danger zones and bodies must be contained within enclosed domestic spaces (or certainly out of sight). In his critical assessment of covid lockdowns, medical anthropologist Carlo Caduff reflects on the importance of orderly appearance, and its reproduction of inequalities:

The lockdown is a political mechanism not simply for the prevention but for the redistribution of negative effects. Lockdowns shift negative effects away from hotspots of public attention to places where they are less visible and presumably less serious. In this way, they are part and parcel of a necropolitics of inequality (Caduff 2020).

Visible bodies are threatening, as pointed out by anthropologist Mohamad Junaid in his analysis of the 2016 military-imposed curfews in Kashmir: ‘in spaces under long-term military occupations, political subjectivity is primarily expressed and enacted as a bodily demand to become visible in public space’ (Junaid 2020: 302). And he continues: ‘the ability to reach such places, run errands, visit people, play or loiter outside, or take a leisurely stroll in public spaces – what in other places might be taken as a given part of daily life and go unnoticed –had become a challenge’ (303). This description of a military occupation is a chillingly accurate account of current worldwide covid curfews. What is more, its operations have been internalised by many of us, as we pursue repressions of the self and of the other in the name of perceived safety (Lancione and Simone 2020). Part II will suggest some ways out of isolation and back into the streets, where public bodies signal healthy communities and where safe public spaces are crowded and sometimes deviant.

Immunity semiotics: encased Churchill statue in Parliament Square London, London June 2020. Photograph: Sabina Andron.

[1] The choice of spelling “covid” in all lowercase letters throughout was deliberate, even though COVID is an acronym which stands for Coronavirus Disease. The reason is to reduce its exceptionality and begin developing a discourse where this word becomes part of common vocabulary and can be used colloquially with the lowercase spelling.

[2] The distinction between the effects of lockdowns and those of lockdown curfews must be emphasized here – as the latter refer only to outdoors movement after a certain time, and indeed I doubt there have been any attempted studies on their effects in particular.

[3] See also examples of German curfew-related case law of administrative courts’ decisions on covid restrictions as a breach of constitutional rights, decided differently and on a case-by case-basis (von Münchow 2020).

Part 1 References:

“curfew, n.”. OED Online. December 2020. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/view/Entry/46020?redirectedFrom=curfew (accessed February 07, 2021).

“Curfew.” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1 Nov. 2016. academic-eb-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/levels/collegiate/article/curfew/628195. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020

-, “Kenya – Nationwide Curfew Extended”, in Africa Research Bulletin, 57 (7), 2020.

Agamben, Giorgio, State of Exception, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Arabindoo, Pushpa, “Life in the Time of Coronavirus: #10 The Lockdown and the Crowd” podcast, IAS Talk Pieces, July 2020 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/institute-of-advanced-studies/publications/2020/jul/ias-talk-pieces-life-time-coronavirus-10-lockdown-and-crowd

Caduff, Carlo, “What went wrong: Corona and the world after the full stop”, in Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 34 (4), 2020, 467-487. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/maq.12599

Chazkel, Amy, “Toward a History of Rights in the City at Night: Making and Breaking the Nightly Curfew in Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro”, in Comparative Studies in Society and History 62(1), 2020, 106–134.

England and Wales Sovereign (1660-1685 : Charles II). (1660). By the king. A proclamation for the suppressing of disorderly and unseasonable meetings, in taverns and tipling-houses, and also forbidding footmen to wear swords, or other weapons, within London, Westminster, and their liberties London, Printed by John Bill and Christopher Barker, printers to the Kings most excellent Majesty. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/books/king-proclamation-suppressing-disorderly/docview/2248520249/se-2?accountid=14511

Junaid, Mohamad, “Counter-maps of the ordinary: occupation, subjectivity, and walking under curfew in Kashmir”, in Identities, 27:3, 2020, 302-320.

Kanbur, Nuray and Akgül, Sinem, “Quaranteenagers: A Single Country Pandemic Curfew Targeting Adolescents in Turkey”, in Journal of Adolescent Health 67, 2020, 296-299.

Korecky, Alexander, “Curfew must not ring tonight: judicial confusion and the misperception of juvenile curfew laws”, Capital University Law Review, 44(4), 2016, 831-872.

Lancione, Michele and Simone, AbdouMaliq, “Bio-austerity and solidarity in the COVID-19 space of emergency – Episode One”, in Society and Space, March 2020, https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/bio-austerity-and-solidarity-in-the-covid-19-space-of-emergency

Lancione, Michele and Simone, AbdouMaliq, “Bio-austerity and solidarity in the COVID-19 space of emergency – Episode Two”, in Society and Space, March 2020, https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/bio-austerity-and-solidarity-in-the-covid-19-space-of-emergency-episode-2

Law, Jonathan (ed), “curfew requirement”, in A Dictionary of Law, Oxford University Press, 2018 https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198802525.001.0001/acref-9780198802525-e-990

Levesque, Roger J.R. (ed.), “curfews”, in Encyclopedia of Adolescence, Springer Science + Business Media, 2011.

McDowall, David, et al. “The Impact of Youth Curfew Laws on Juvenile Crime Rates”, in Crime and Delinquency, 46 (1), 2000, 76-91.

Sandford, Alasdair, “Coronavirus: Half of humanity now on lockdown as 90 countries call for confinement”, Euronews, AP, AFP, 3 March 2020, https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/02/coronavirus-in-europe-spain-s-death-toll-hits-10-000-after-record-950-new-deaths-in-24-hou (accesses 7 Feb 2021).

von Münchow, Sebastian, “The Legal and Legitimate Combat Against COVID-19: German Curfew-related Case Law”, in Connections QJ 19 (2), 2020: 49-60.