On Borders and Thresholds: the recognition of differences between exclusion and protection

Azzurra Muzzonigro, Italy

15 January 2021

Dwell the Threshold, PhD thesis by Azzurra Muzzonigro.

To dwell the threshold and to ‘become other than oneself’

As an architect and an urban researcher, I have been investigating the spatial politics of the border for quite some time: my PhD thesis Dwell the Threshold, spaces and practices for a plural city[1] focused on spaces of threshold as the opportunity to create new hybrid identities out of the encounter among differences. The whole argument is centered around the idea that the border space between two distinct worlds should be thought of as a thickness (Zanini, 1997), rather than a line. In the same way ‘the margin’ as a field of research stems from the richness that arises from the encounter of different environments (Clément, 2004). It is in that depth that it is possible to find the words to ‘become other than oneself’ (Bhabha, 1988).

This thickness of the border contains acts of simultaneous separation and connection. This threshold represents ‘the point where two different worlds meet’ (Stavredes, 2010: 16). Inhabiting this distance that unites and separates different entities, allows for encounters and hybridizations between differences. It is necessary not to increase the threshold, thus transform it into hostility, or eliminate it. Doing so would lead to the assimilation of differences: ‘the encounter is achieved by maintaining the necessary distance and crossing it at the same time’ (ibid: 16-18).

Establishing a boundary thus becomes the frontier for social and cultural transformation as, like any limit, it implies the possibility of being crossed. The thickness of the boundary reflects the space given for negotiation between two distinct cultures. I will explore two forms of this negotiation in case studies of the Roma in Rome and the Yanomami in the Amazon forest of Brazil.

Roma in Rome: fighting invisible borders of exclusion

At the time in which I was developing myresearch on thresholds, I was working closely with Roma communities in Rome. Their condition of ‘forced nomadism’ produced by a series of evictions in the city of Rome made me and my colleagues deeply consider the essence of borders. For many Roma communities, the existence of Nomad Camps made visible the politics of exclusion. The camps took the spatial form of informal settlements and formal camps provided by the city administration.in the vast majority of cases these functioned as ghettos. Whether the border surrounding the camp was visible or invisible, there was the lack of recognition of the specific identity of Roma people in the city. Their radically different mode of existence was considered a threat to the population inhabiting the surrounding neighbourhood. Therefore they were unwanted and untolerated by their neighbours.

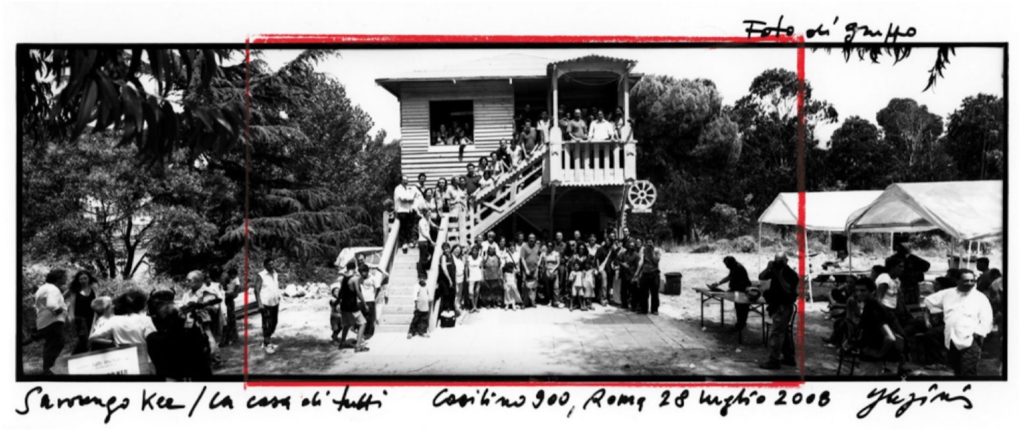

Savorengo Ker / the house of everybody. Photo by: Giorgio de Finis.

As researchers our question at the time was: how can we transform a Roma camp from a ghetto to a neighbourhood? How can we knock down the invisible wall of prejudices and stereotypes that imprisons the Roma in a vicious circle of marginalisation and crime? We decided to focus our efforts on opening up the camp and transforming the invisible border into a threshold. Roma kids would go to school outside the camp and build relationships with non-Roma (gadjé in Roma language) kids, and at the same time camps would become multicultural neighbourhoods, like Chinatown or African districts, where the uniqueness of Roma culture would become a richness for the whole city. While there were concerns that by opening up the border of the ghetto the Roma would lose part of their traditional identity, there are advantages to becoming part of a wider urban community. In light of these questions and research, the project Savorengo Ker, the house of everybody[2] was born. Together with Università Roma Tre, Stalker and the Roma communities, a prototype of a house in scale 1:1 was built to demonstrate that Roma people can respond to their own housing needs if the opportunity is given to them. Through this practice the invisible wall that confines the Roma can be deconstructed, replacing prejudice with knowledge and invisibility with mutual recognition. Unfortunately the house didn’t have much luck: its construction hasn’t been recognised by the public administration and on a rainy night after three months of abandonment, it was burned down, and with it the dream of a common ground for coexistence between Roma and gadjé.

Yanomami in the Amazon forest: fighting for borders of recognition

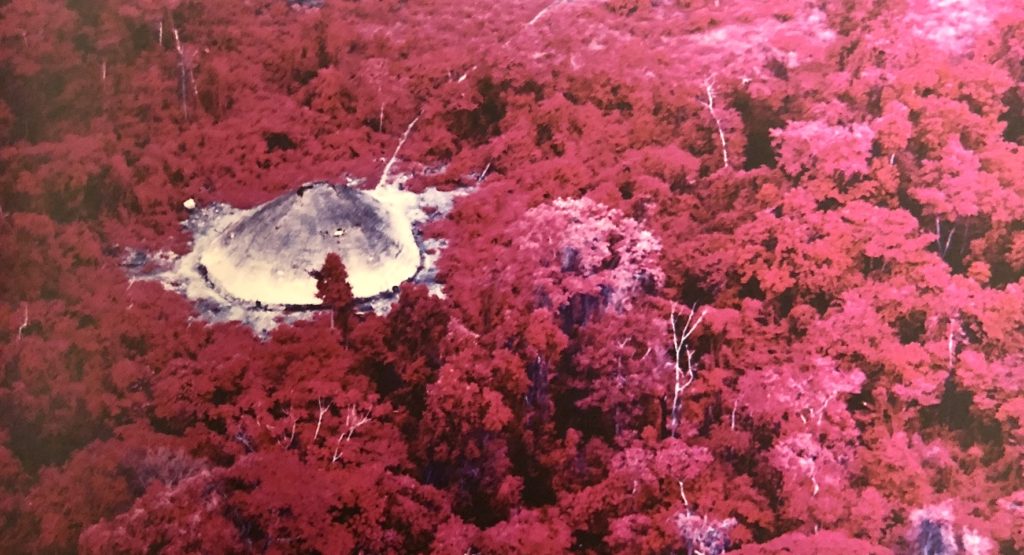

As a comparison, I will consider the concept of a ‘border’ from a perspective that recognises its importance as a tool for protection and resistance[3]. In the past few years I have had the opportunity to look closely at the case of the Yanomami population living in the Amazon forest on the border between Brazil and Venezuela. The Yanomami have been inhabiting the forest for centuries with no contacts with other populations for a very long time, until their land, rich in natural resources became the object of desire of the voracious garimpeiros. In the 1970’s the Yanomami struggle began in response to the construction of the Perimetral Norte, a road which was built under the pretext of defending the northern border of Brazil. In reality its construction was instrumental to exploit the Yanomami territory, which was rich in gold, uranium and cassiterite. Shortly thereafter the area was invaded by gold prospectors and mining industries: the extraction process polluted the rivers while the labour force brought diseases that decimated dozens of Yanomami communities. What follows were years of hard battles until the end of the military dictatorship in Brazil in 1985. With the appointment of the new Brazilian president – on the eve of UNCED, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 – a territory of almost 10 million hectares was declared as property belonging definitively to the Yanomami. These 10 million hectares were marked with a line drawn on a map, a border.

Maloka Yanomami. Photo by: Claudia Andujar.

Unfortunately, the fight did not end there. January 2019 saw the appointment into office of Jair Bolsonaro, a member of the far-right Alliance for Brazil party who publicly spoke of the extermination of indigenous peoples. This prompted a new season of violence against the indigenous people and against the Amazon forest The Funai (the National Indian Foundation, the Brazilian government body that deals with indigenous protection policies) was transferred from the Ministry of Justice to the Ministry Woman, Family and Human Rights.The assignment and demarcation of land, once under the responsibility of Funai, became the task of the Ministry of Agriculture, which opened the territory to exploitation and contamination by industry once again. These acts gave legitimacy to violent and predatory behavior towards indigenous populations and the forest, portraying both people and forest as an obstacle to development.

Bruce Albert, anthropologist and author with Davi Kopenawa of the book The Falling Sky, published in Italy in 2018 by Nottetempo, speaks about the indigenous population of the Amazon forest as the sacrificial victim for the idea of progress and primary accumulation of wealth perpetrated by the West, an idea that began with the extraction of gold, silver, raw materials and then oil, to the detriment, now as then, of the populations who lived and still inhabit the forest (Kopenawa and Albert, 2018).

The Yanomami show us another way of living the planet, very distant from ours, in balance with other forms of life and the forest. Their existence makes us reflect on the profound meaning of our being in the world as human beings: it allows us to watch western civilisation from outside, through the eyes of those who inhabit the earth with a light step, treating it not as a property or a resource to be exploited but as a gift to be respected, Under this light their existence constitutes an advantage for our culture as well: in times of climate crisis their experience and their cosmology could become a powerful tool of transformation of the extractive, illuminist and anthropocentric attitude of the western civilization which is rapidly leading the planet and its forms of life into a dead end.

The Yanomami struggle is therefore more urgent now than ever, and much of it plays around the defense of the border of the Yanomami territory. The recognition of the border has been a great political achievement for the Yanomami because it recognises their right of existence in the first place, as well as their sovereignty on their land. In this case establishing the border is a tool for survival and resistance for them but a tool for protection of diversity for the whole of humanity.

By presenting these two cases, the Roma in Rome and the Yanomami in the Amazon forest, two different attitudes towards the border emerge. In both cases the presence of the border is important to prevent total assimilation of the minority population. In the case of Roma, being ‘guests’ in somebody else’s land, the issue is about perforating the invisible wall of exclusion by expanding the width of the border to a permeable threshold as a way to have their existence respected by the neighbouring population and create common grounds for coexistence. In this context there are greater advantages to social inclusion by creating a threshold to share values. In contrast, the Yanomami require a defined border as a tool for protection of their ancestral presence in the forest. The presence of a distinct border provides grounds to protect their land from becoming the object of a pervasive colonial and extractive attitude by their neighbours who want to claim sovereignty of their land for material gain. As Stavrides says: “encounter is realised by keeping the necessary distance and crossing it at the same time”, this encounter happens in space by means of the border, which is a powerful tool to set the rules for coexistence among differences.

[1] Dwell the Threshold, spaces and practices for a plural city was the Phd thesis I developed at Università degli studi Roma Tre under the supervision of prof. Francesco Careri, based on a research project I started within the MsC in Building and Urban Design for Development at the UCL London under the supervision of prof. Camillo Boano. For reference see here.

[2] Savorengo Ker/the house of everybody is an experimental self-building house at the Campo Rom Casilino 900, in Rome, realised by the collaboration between the Roma community of Campo Casilino 900, Stalker and Dipsu / Università degli Studi Roma Tre. The experimental housing prototype has shown that it is possible to realize, at the cost of a container, a real ecological and sustainable home that meets the living standards and building codes. The house was inaugurated on July 28th, and burned by unknown people on December 11th 2008. For reference see here.

[3] Parts of this paragraph on Yanomami border were originally published on Artribune in January 2020.

References:

Bhabha, H., 1988, The Commitment to Theory – New Formations NUMBER 5 SUMMER I 988.

Clément, G., 2004 Manifest du Tiers paysage, Editions Sujet/Objet, Quodlibet.

Kopenawa, D., Albert, B., 2018, La caduta del cielo. Parole di uno sciamano yanomami, nottetempo, Milano.

Nougueira, T., 2019, Claudia Andujar, La Lotta Yanomami, Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain and Triennale Milano.

Stavrides, S., 2010, Towards the City of Thresholds, Creative Commons, ProfessionalDreamers.

Zanini, P., 1997, Significati del Confine. I limiti naturali, storici, mentali. Bruno Mondadori. Milano.