Animated skins –part 2

Albert Brenchat-Aguilar, UK

12 April 2021

This is Part 2 of a two-part article. Read Part 1 here.

Are some of us hungry for skin or is our skin hungry? The animated video illustration brings me to the animacy of the skin.[1] I wonder if our skins have been finally fleshed out in our minds as a frontier space that not only communicates the body and the environment it separates but also contains a life of bacteria, fungi and viruses on its own;[2] as a frontier that, once it has been formulated as such in our minds, enables a space for life. The bacterial life of the skin consumes both the inward- and outward-facing sides of the boundary and grows in a differential entangled relation of decay and growth; if the bacteria or the virus grow disproportionately and unregulated, the contained human decays, conceptually transforming the skin and its microbiome into a horizon of interiority and exteriority[3] that can be appreciated in the bacteria-based consumption of faces by sculptor Mellissa Fisher.

Mellissa Fisher, Microbial Me, 2015.

What is the relationship between different hungry skins? The skin microbiome maintains these stable horizons of interiority and exteriority. The perception of the skin and its viral categorization is a social construction as is the classification of different skin identities around class, gender, sexuality, race, age and others. Some skins could be seen as too animated, as if they could devour the boundaries between themselves and other entities. Skin hunger works by the same logic of any other hunger chain: some humans and their skins in the tail produce antiviral products, some others consume these first, and some have to live with the rejects, the excrement of that digestion of skins. This essay’s suggestion of the patterns by which skins are perceived to digest themselves, each other, and corona shapes on them draws from Wazana Tompkins’ literal and metaphorical histories of US 19th century mouth- and anal-focused digestion of Black and Asian bodies. In addition, the presence of the virus in the air and the skin itself reinforces the consumption of the skin through all orifices of the body including nostrils, eyes, and genitals, being the whole skin both an intermediary medium of digestion and the digested entity.[4] Or in other words, the skin becomes a frontier space that is both a mediation and a sign of difference of the bodies’ virality. This, as Wazana Tompkins’ argues, trespasses the ‘epidermal ontology of race’, and I would say of age and others, as the assigned virality and consequent damage of the skin presents the violence inflicted both inside and outside the body.

This is indeed no less complicated by the agency of those that feel the willingness and the capacity to touch the other as a form of or mediation to consuming their skin. Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin’s installation, workshops, and writings on ‘Universal Skin Salvation’, comment on the production of Lactic Acid and its use in ‘K-beauty [Korean cosmetic industry] products as a whitening agent’ producing a porcelain-like skin.[5] As Shin explains, such skin surface ambition is entangled with racial fetishism and gender desire, colonialism, and warfare experiments.[6] Most importantly for this essay, Shin presents Lactic Acid ‘found in sour milk, in muscles, and in fermented foods like Kimchi’ as a literal and metaphorical consumption and extraction of human bodies for the smoothness of the skin that is aesthetically entangled with anti-bacterial approaches that transform the skin into an object of consumption.

Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin, 'Universal Skin Salvation', 2018-ongoing.

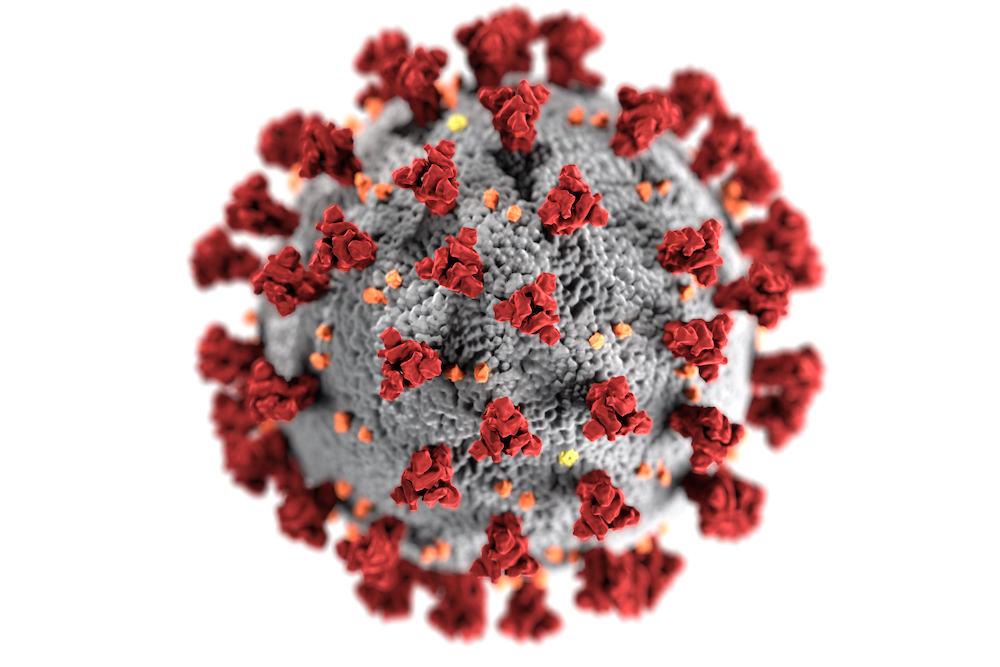

In the virus, the spikes are the source of anthropocentric concerns for they are the ones attaching to the cells living in our bodies. And these spikes are what stand out in Navarro’s image, what seems to be non-human in the humanity of his caricature: an appendix, a form of excess or ornament. These two words reify a 20th-century problem with the capacity of any entity to admit its multiple constitution. As in classical architectural discussions between pre- and post-war modernism (i.e. Adolf Loss’ rejection of ornament versus the defence of ornament as part of the object itself by Brutalists), here the ornament lies in the tension between an external agent and a part of the body, problematized by the aliveness of such ornament. Ornament and excess are ever present in histories of racism and sexism that, through different mechanisms, transform the identified Other into things either for consumption or rejection.[7] Additionally, the non-human-human agentic entanglement of the microbiome makes the skin a frontier space not only of the body but of conceptions of the human itself and essentialist objectification.

The profiling of viral identities and landscapes in the media might render some socially constructed ‘skins’ as ‘too’ animated and hungry, to the extent that they become a threat. Some skins are treated as Navarro’s human-virus since the media has, in many cases, profiled certain viral identities around intersections between race, class, gender and occupation, and of course around age. Beyond overtly racist appeals to ‘yellow peril’ in all its forms that triggered defence campaigns such as the #ImNotAVirus and #EndTheVirusOfRacism, the media has perpetuated viral identities through unconscious bias. In the interest of image representation in this paper, I highlight the British East and South East Asian Network reporting that ‘Out of 14k images pulled from various UK news outlets reporting on COVID-19, 33% of a sampled subset were found to have images of ESEAs unnecessarily’.[8] Generally, intersectional identities —specifically, in the UK, elder Black and Latinx working class female key workers— have been useful to describe categories of vulnerabilized subjects, always mindful of their social construction. The hunger for skin has indeed most affected the elders who are nonetheless affected by the inadvertently excessively homogenised category of vulnerability.[9]

I don’t know if, and what hand sanitisers killed before, during and after rubbing them on myself. We’ve sanitised our skins as we sanitise the walls, pavements and railings of our buildings. Our connection between our bodies and the built environment has surprisingly increased through sanitation. Of course it is not only the destiny of our sanitisers that concerns me but their social histories and material origins: think of chemical interest of soap producers since the 19th century; or past and present idealizations of sanitation and the myriad histories of xenophobia against other humans and non-humans that they trigger.

The spikes of the coronavirus and the rendering of its surface by CDC.

In Corona Tales, the images of coronaviruses were replaced by the photographic album of Martinez. With this edition her stories regained the human quality that they intended: situated in the technologies and spaces of Northwest Spain in 1918 until the present. Did we lose something by not looking closely at SARS-CoV-2 in this edition? Maybe, I suggest, we’ve been looking at the virus with the wrong detail and angle, always in isolation. Whilst the body of the virus is rendered spheric, textured, soft, inorganic, its spikes are highlighted in the warm colours of danger. Amongst their hybrid capacity for connectivity, it is the grey dirt of the body it grows from: hybrid as queer and lacking identity. Failing in our capacity to engage with the non-human threat in a different way, we might better stay with Martinez’s texts and personal portraits that promote a rather more humanistic view. I speculate with two possible ways forward: first, that knowledge of our own microbiome and bodily bacterial constitution would make these viral images more connected to our bodies —for example entangled in follicles and sweat glands, or the textures of different tissues. Second, an acknowledgement of our own destructive action toward the environment —thus toward our own bodies and those of others— could render the virus with the same care that we devote to the human figure: not so much a threat to the human but a threat to our present form of life. That is, acknowledging that our present lifestyle and ways to vulnerabilize certain sectors of the society have killed more than any virus (if the virus could be conscious of its acts) could have ever imagined.

You can see part 1 of this essay here.

Appreciations: This text was partially presented in the introduction of one of the seminars on New Normal Materialist Decay at the Institute of Advanced Studies, UCL in September 2020 –February 2021. I also have enormously benefited from organising Covid workshops —the concept of Vulnerabilization is drawn from Boaventura de Sousa Santos in these workshops. I want to thank all the speakers that took part in these series and especially thank those that have specifically shaped my piece with their ideas: Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin, Mellissa Fisher, Mel Y. Chen, and Anne Anlin Cheng. I would also like to thank Gaby, Emily and Manuela for their thoughtful editorial directions, and to Eduardo Navarro for agreeing to share their images with me.

[1] I’m thinking here along the lines of the critical methodologies in Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect, Perverse Modernities. (Duke University Press, 2012).

[2] For a general review of the microbiome in healthy and sick patients see Allyson L. Byrd, Yasmine Belkaid, and Julia A. Segre, ‘The Human Skin Microbiome’, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16.3 (2018), 143–55 <https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.157>.

[3] in Reza Negarestani’s conceptual framework for decay. See Reza Negarestani, ‘Undercover Softness’, in Collapse (Urbanomic, 2012), VI <https://www.urbanomic.com/chapter/collapse-vi-undercover-softness-reza-negarestani/> [accessed 9 February 2020].

[4] Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the 19th Century (NYU Press, 2012), JSTOR <https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg65w> [accessed 25 August 2020]. Wazana Tompkins refers to her research as ‘reading orificially’ although the orifices in the end are limited to the functions of food digestion — see ‘Introduction: Eating bodies in the 19th century’.

[5] ‘Universal Skin Salvation — Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin’ <https://jaeyeonshin.com/Universal-Skin-Salvation> [accessed 1 April 2021].

[6] Shin refers to the relationship of Lactic Acid and Retinol A with experiments in the Korean and Vietnam wars.

[7] In terms of Western portrayal of Asiatic femininity and ornament see Anne Anlin Cheng, Ornamentalism (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). Also reading the work of Christina Sharpe, Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Mel Y. Chen, Alexander Weheliye and many other critical race and gender theorists.

[8] See the resources for the China Debate workshop I co-organised at the Institute of Advanced Studies, UCL for more information and media portrayals. UCL, ‘Debate Theme 3: “China’s Covid” and Renewed Racist Attacks against East Asians’, CCHH: China Centre For Health And Humanity, 2020 <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/china-health/china-and-covid-19/debate-theme-3-chinas-covid-and-renewed-racist-attacks-against-east-asians> [accessed 3 April 2021].

[9] See for example: Liat Ayalon, ‘There Is Nothing New under the Sun: Ageism and Intergenerational Tension in the Age of the COVID-19 Outbreak’, International Psychogeriatrics, 32.10 (2020), 1221–24 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000575>. Deanna Vervaecke and Brad A Meisner, ‘Caremongering and Assumptions of Need: The Spread of Compassionate Ageism During COVID-19’, The Gerontologist, 61.2 (2021), 159–65 <https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa131>.